The Cumann na mBan: The Irishwomen’s council

Cumann na mBan logo

When I began to research the Irish revolution in more detail, I came across brief mentions of the women of ‘Cumann na mBan’, The Irish women’s council.

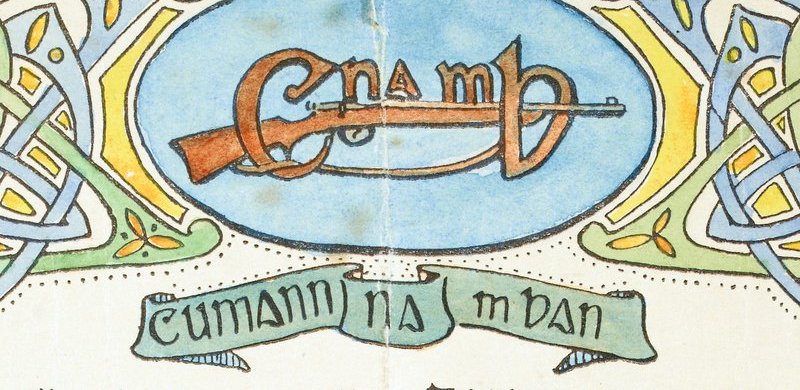

Founded in 1914, Cumann na mBan (pronounced cu-mann na mahn) was initially made up of suffragettes, trade union activists and socialists who felt disenfranchised by the all-male National Volunteers. At its heart was social change, rights for women, and the right of Ireland to form a Republic – by use of force by arms if necessary.

A newspaper ad drafting members for Cumann na mBan

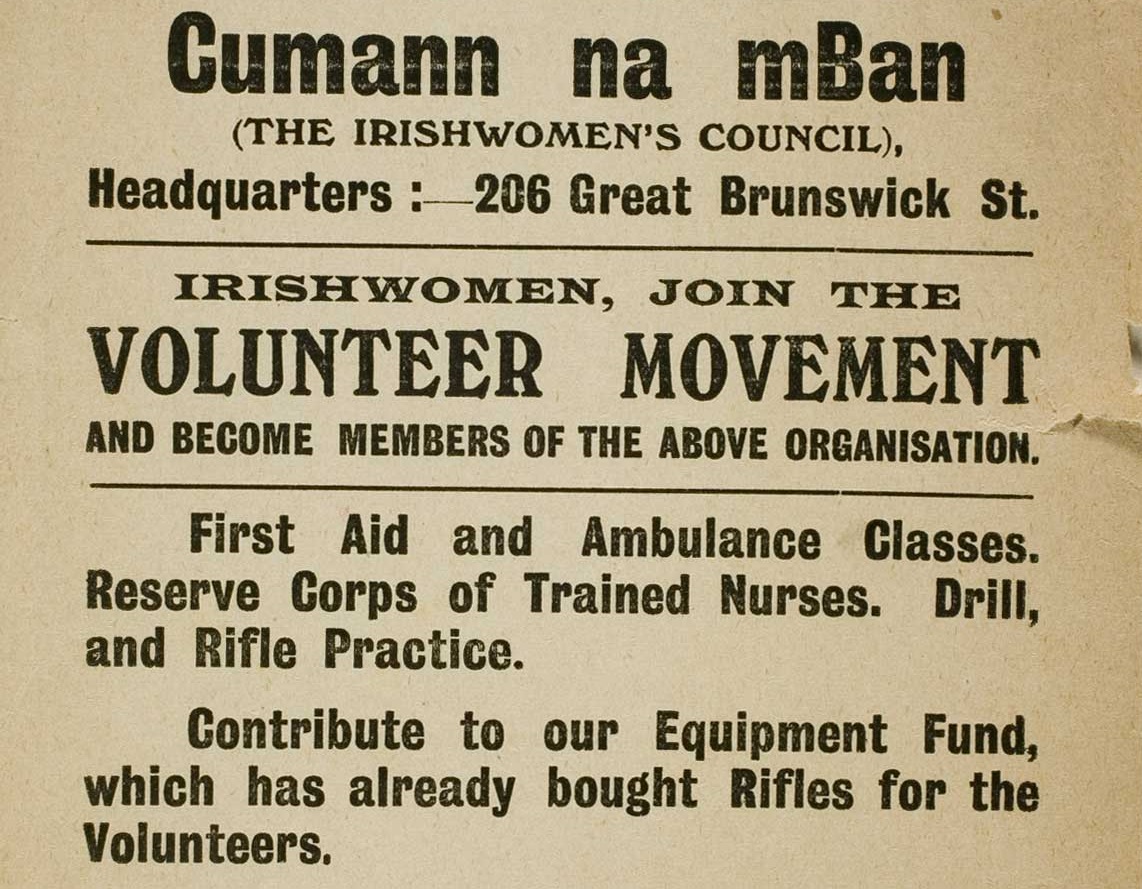

In the lead up to the 1916 ‘Easter Rising’, Cumann na mBan officially became a para-military force, along with the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army. In fact, on the day of the Rising, leading Cumann na mBan members were involved in storming the General Post Office armed with revolvers, and sowing insurgency throughout Dublin, helping to spark the Irish Revolution.

I had the privilege of speaking to Dr Hélène O’Keefe, currently completing a DPhil in Irish History, who led me to the best historical source: The Irish Military Service Pensions Collection.

Recorded on yellowing and closely typed paper, I found first-hand accounts of the women across West Cork who had risked their lives to support the Irish War for Independence against the British. This research directly inspired the characters of Nuala and Hannah Murphy, as well as the other brave female characters in the 1920 sections of ‘The Missing Sister’. Ellie Sheehy of West Cork was one of these brave women and is mentioned briefly in ‘The Missing Sister’. From her pension report we can see the extent of her tireless work:

‘There was a dump for arms near her house about three fields away… a box of bombs and a box of ammunition. […] She brought them to her house after the military passed… She helped to equip column-men numbering about 40.’

Through the characters of Nuala and Hannnah I was able to show a little of the activities carried out by Cumann na mBan. As well as carrying secret messages, acting as spies, hiding arms and providing safe houses, they nursed, fed and clothed the volunteers.

Women of Cumann na mBan training with rifles.

As Ambrose points out in ‘The Missing Sister’, there are few personal records written by women from the period of the revolution. While we have a number of accounts from the men of the Flying Column, for example, the women’s stories are still to be told. I hope that Nuala and Hannah’s stories have inspired my readers to discover more about this fascinating part of Irish history.